Lecture Nine for JOUR1111 was predominantly

concerned with News Values.

What do we mean by News Values?

Essentially, News Values can be defined as the

degree of prominence a media outlet gives a story and the attention that is

paid by an audience (as a result). Stuart Hall interestingly described News

Values as ''the most opaque structure of meaning in modern society." He

went on to state that "Journalists speak of 'the news' as if events select

themselves ... Yet of the millions of events which occur daily in the world,

only a tiny proportion ever become visible as 'potential news stories': and of

this proportion, only a small fraction are actually produced as the day's

news." In regards to News Values there are four things which are very

important: (1) Impact, Audience Identification (2), Pragmatics (3), and Source

Influence (4).

Are News Values the same across different news

services? Countries? or Cultures?

The answer to this question is a resounding no.

Effectively, news values vary significantly from news service to news service,

country-to-country and culture-to-culture. It is, however, an old saying in

Journalism circles that, "if it bleeds, it leads" - a grotesque

thought indeed. A more modern thinking is the idea that "if it's local, it

leads." This philosophy is adopted most evidently by Channel Nine and

Channel Ten who focus their news on the hyperlocal.

"Newsworthiness"

Harold Evans, former Editor of The Sunday Times

once stated, "a sense of values" is the first quality of editors -

they are the "human sieves of the torrent of news." Evans is

essentially saying that what is most important for an Editor is to be able to

identify what good news is. He created the idea of "The College of

Osmosis" which suggests that once in the workplace one, from experience,

knowledge and other factors, will be able to identify what good news is,

without receiving guidance from anyone. Veteran Television Reporter and

Journalist John Sergeant reinforced Evans' sentiments, opining that

"Journalists rely on instinct rather than logic" when to comes to

defining a sense of news values.

Galtung and Ruge identified 12 factors of

newsworthiness. They analysed International News to discover what they describe

as the "common factors" of newsworthiness. The factors were as follows:

1. Negativity

2. Proximity

3. Recency

4. Currency

5. Continuity

6. Uniqueness

7. Simplicity

8. Personality

9. Expectedness

10. Elite nations or people

11. Exclusivity

12. Size

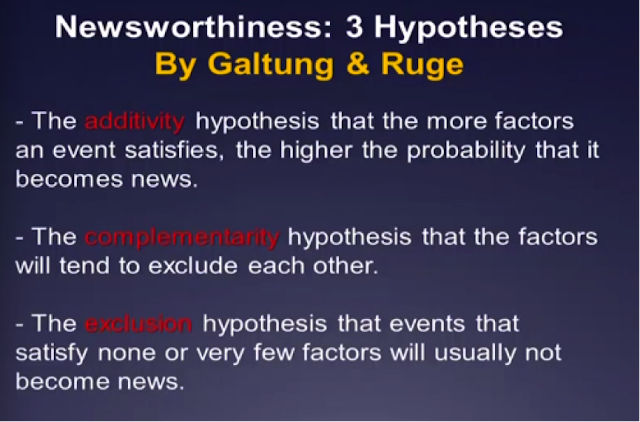

They also formed three hypotheses around these

common factors:

Golding and Elliot in 1979, identified different

factors they felt were common to news that appeared of "worth". They

were drama, visual attractiveness, entertainment, importance, size, proximity,

negativity, brevity, recency, elites and personalities.

In 2001, O'Neill and Harcup outlined what they

saw to be the common factors of newsworthiness now in modern society. They

placed particular importance on the factors of: the power elite, celebrity,

entertainment, surprise, bad news, good news, magnitude, relevance, follow-up,

agendas of outlets/organisations.

Further, a year later, in 2002, Judy McGregor

condensed the relevant factors of newsworthiness into only four common factors:

visualness, conflict, emotion and celebrification of the journalist.

Interestingly, Dr. Redman ended this section of

the lecture by convincingly arguing that there now exist, in contemporary

society, new news values which have yet to be identified. These include:

Terrorism, the Global Financial Crisis, Health, Fitness and Diet, and anything

in relation to the Environment.

|

| Healthy Eating is now a concern of many modern Australians and as such is arguably very "news worthy" |

Threats to Newsworthiness:

Downie and Kaiser argue that a threat of

newsworthiness is lazy and incompetent journalism. Such a fact is exemplified

by their statement that, "too much of what has been offered as news in

recent years has been untrustworthy, irresponsible, misleading or incomplete."

Conversely, Davies argues that a threat to newsworthiness is tabloidisation:

"...media falsehood and distortion; the PR tactics and propaganda; and the

use of illegal news-gathering techniques." Further, Rowse maintains that a

significant threat is posed by hyper-commercialisation as "media mergers

are rapidly creating one huge news cartel ... controlling most of what you see,

hear and read. These mergers further corrupt the news process."

Has the audience moved on?

Things like citizen journalism now means that,

in some respects, the power held by the media outlets is beginning to shift.

Jay Rosen supports this notion stating to the Media outlets in general that,

"you don't control production on the new platform which isn't one-way.

There's a new balance of power between you and use ['the audience']. The people

formerly known as the audience are simply the public made realer, less

fictional, more able, less predictable."

Future of News Values?

The moving on of the audience has raised many questions

for the future of News Values. Indeed, what will tomorrow's News Values be?

What governs what a media organisation sees as news worthy?